When a life is saved, so are the memories it will make. They’re plucked from oblivion and allowed to happen. This is what Risa Jampel wanted us to know from the start.

We were gathered for Sunday brunch on the 21st anniversary of the almost-death of Risa’s husband, Henry, and his rescuscitation on the floor of a shower at a swim club in Baltimore. Henry, who is 65, calls May 16 his “rebirthday.” At 21 he’s now a full-grown second-chance adult.

“On Friday I started thinking about this party,” Risa told 20 people at outdoor tables under an awning. She said she’d been driving alone, listening to music—“the kind of stuff you’d listen to at your kids’ weddings” (of which there’d been two in recent years, with another coming up)—and musing how the party would mark a turn in the Covid-19 pandemic.

She paused.

“And then I started to think, really, about why we were having it. All of the wonderful things we’ve been able to do in the past 21 years having Henry with us, like those two weddings. How it wouldn’t have been the same if he weren’t here . . . I could feel the tears rolling down my face. I hadn’t done that in a long time . . . Our kids would have been without a father, and I would have been without a husband. We are just so grateful.”

That would have been enough said for the whole event. But, of course, it wasn’t. There were dozens of memories, big and small, to recount.

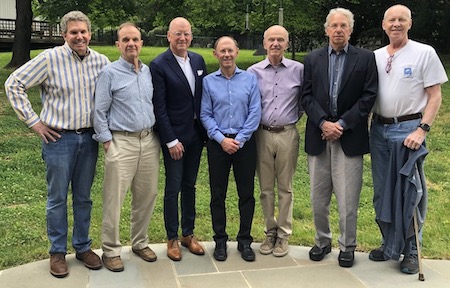

Two of the four people who’d resuscitated Henry, and the person who discovered him and called 911, had remained in Baltimore. One of the other resuscitators had moved to Texas and become the president of a medical school. The fourth had moved to Hawaii, but recently returned to Maryland. About work and children, politics and the pandemic, there was a lot of ground to cover.

The event that brought us together, to no surprise, featured prominently in the conversation.

As is often the case in youngish victims, Henry was unusually fit when he suffered sudden cardiac arrest. In fact, he’d completed the Hawaii Ironman triathlon less than a year earlier. The unlikeliness of his collapse is one reason it’s burned into the memories of the people with him that morning in 2000. But it was curious how inconsistent the memories were.

Who started the CPR? Did Henry’s wife arrive before or after the long-delayed paramedics? Was an IV line started and drugs administered before he was carried away in an ambulance? There was surprising uncertainty in the answers.

One thing no one doubted was that the arrival of an automated external defibrillator (AED) made the difference. On the third shock, Henry’s pulse returned, 27 minutes after he’d gone down. It was as close to a miracle as one could expect to see in a lifetime—there was agreement about that, too.

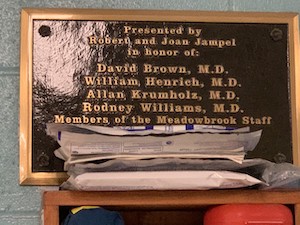

Soon after Henry recovered, his parents gave an AED to the swim club, along with a brass plaque thanking the four resuscitators, of which I was one.

There’s another way in which Henry Jampel’s survival serves the cause of memory.

Speaking only for myself, May 16, 2000, is one of the half-dozen most important days of my life. I will try not to forget its many lessons. Here are a few.

Life can change in a moment, so try to be ready. Don’t be embarrassed. Have courage and don’t stop. Do chest compressions deep and fast. Know where the closest AED is.

And be grateful, for all sorts of things. Especially don’t forget that.

By David Brown

Henry Jampel, MD, MHS, is Professor of Ophthalmology, Wilmer Ophthalmological Institute, Johns Hopkins Hospital. He also serves as Chair of the Sudden Cardiac Arrest Foundation Board of Directors.